Holocaust-Mahnmal

Stelen in Berlin

The Holocaust Memorial

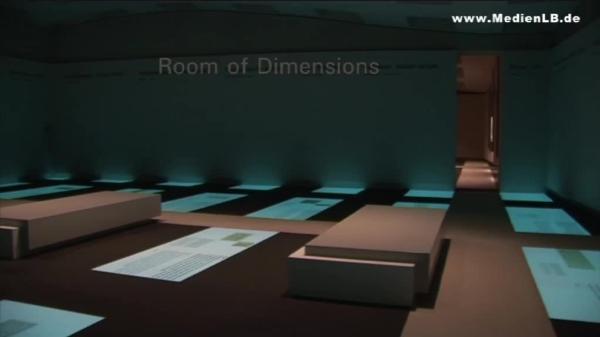

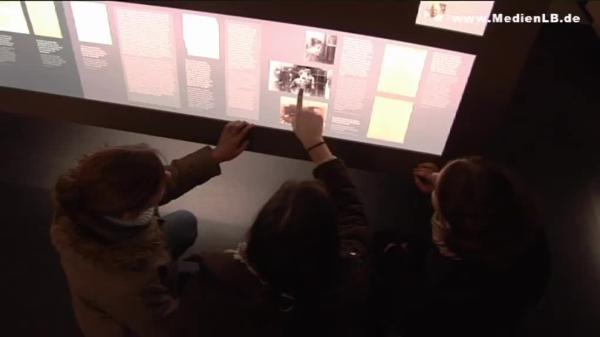

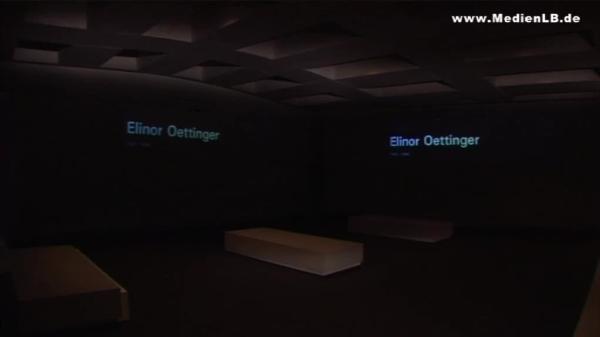

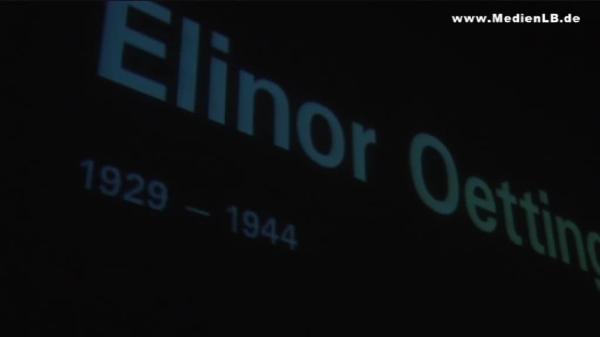

1. The Memorial Walking down here, it gets narrower and narrower, it gets more and more stifling, it's like although there is an exit, okay, but not back then… I'm just going to let it all sink in on an emotional level, because it's as if all sound is receding, it feels quite tranquil to me… I find it rather arbitrary. There's a sense of no escape… From the outside it appears so useless and not really attractive… From the outside you can't see at the whole impact the interior has. Yeah, it's at the lowest point that the impact becomes noticeable. Well, when you start here in this flat part and then move down to the lower area, well, then you're right inside immediately and then you get these associations… It gets narrower and narrower – almost like a tomb… I sort of wish there was a definite statement on what it's really supposed to be, or whether they sort of avoided doing so, i.e., "if you don't realize what it is, then you're simply too stupid", or something like that… Well, I did see them as stone slabs, as grave stones… Menacing. Also the fact that they're tilted and sometimes so cramped. But I know, I can get out of here. But they didn't get out. The Victory Column or the Soviet War Memorial just around the corner from here are conventional memorials. But Eisenman deliberately said: "The only way to approach the Holocaust, this crime and also this incalculable loss of human life is through an abstract work of art." For this there is no definite message, only a field of stelae, where you can walk around as you like and by walking through it, people should remember, should have associations. We don't tell them what to think, or how they should respond. And everyone finds its own interpretation. There is no getting around that – pure and simple. You cannot sidestep that fact. And that's the whole idea. Where else do you think it could be, eh? If not right in the middle of the city? But I feel it is critical that it is here right in the centre of things. It's like, for anyone living in, or anyone coming to Berlin, they have to go by here. Well, I feel that the land itself is so valuable, I wonder whether it's really worth it. Well, putting it somewhere out in the suburbs is not an option – then you may as well park it somewhere out in the middle of nowhere. The most important thing for us was that we are raising the Jews above Adolf Hitler. We are placing this memorial right where he killed himself, where his bones lie. That's what we wanted – and we got it. The Information Centre informs people what this memorial stands for. And after visiting the Information Centre they have a completely different view of the Field of Stelae. When visitors enter the Information Centre from the Field of Stelae, the first thing they see are the six portraits behind me. Those exhibited on the front wall of the entrance foyer are in such a prominent place because it was particularly important to me to demonstrate one of the principles of our exposition - a principle that applies just as much to the four subsequent rooms – it is referred to as the principle of personification. This involves our showing the history of the Holocaust from the viewpoint of the many individuals who were persecuted and murdered and then grouping the general information around it. This timeline should give visitors an opportunity to gather fundamental information on the chronology of events of the Holocaust. Before visitors enter the actual exhibit, which focuses on the personal fates of the victims, they have the opportunity – via texts and images – to follow each of the separate stages of persecution, how that persecution escalated. And one of these pictures where this personification principle becomes especially clear, is this one here. It's a picture of Arnold Blitz, one of the survivors of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, taken in May, 1945 in Berlin on the Kurfuerstendamm boulevard. And he's evidently switched clothes with another fellow prisoner who survived – he wears the prisoner's pants, the other fellow the prisoner's top. They're clearly recognisable as concentration camp prisoners. It was Mr. Blitz who obtained a camera to have themselves photographed very demonstratively, making a visual statement: "We are still here, we survived". And this, in May, 1945 in Berlin on the main boulevard, the Kurfuerstendamm. There were one or two texts that were especially difficult to write: these were the texts on 1941, on the Fall of '41, because Fall '41 was the critical phase, the months in Fall '41, the critical phase where a plan, no matter how it had been put together beforehand, was then actually put into action. And this plan was implemented in occupied Poland in the Summer of 1941 where the situation in the ghettos was already dire. This misery was created by the Germans themselves, the Jewish ghetto inhabitants were not allowed to work, were not allowed to earn any money, they were provided for, but badly, many were sick, many were starving. And as this misery was immense, and the German authorities had already announced that additional groups of Jews were to be transported to the ghettos from Germany, the local National-Socialist authorities began to implement a plan that did not ease the situation for the ghetto inhabitants, did not give them more freedom and finally release them, but rather implemented a plan consisting of murdering these people. And to display this, so to speak from the viewpoint of a forced act, as such the perpetrators claimed it, and felt it, but which naturally was nothing of the sort – that was very difficult. Because our task was to make it understandable for visitors that there was no such necessity. This was all planned, and these plans were simply – and consciously – stepped up further and further. 2. Room of Dimensions Each of the four rooms has a different thematic focus and this is reflected in the varying designs – corresponding to the respective focus. And here in this room, which is all about the dimensions involved, the sheer number, the 6 million people who were obliterated, what better way to express that than through empty space? This room is void, almost completely emppy of three-dimensional objects and the loss and the absence of these people can only be expressed through this emptiness. The idea to present these very personal and private quotations on the ground, formed as I was imagining what it's like when someone reads a source of this nature, it affects you so strongly that you look down, you lower your eyes, which helps you to look within yourself, helping you to contemplate it all more clearly – and I simply feel it's easier to confront this on an emotional level with your head bowed, than if your head is upright. 3. Room of Families The quotation that again and again moves me the most is the farewell letter here of the 12 year old, that knows she is going to her death and is bidding her father farewell. Because she knows that she will never see him again. In this room, I have taken up the formal aspect of the Field of Stelae practically 1-to-1 and continued it, so that here, it looks as if the stelae of the memorial are growing through the ceiling, opening up here, and allowing the victims to speak. At the same timethey also symbolise, these stelae represent the fates of families, and usually, families are the root or foundation of any society. These families here had their contact to the earth torn from them, meaning, they remain suspended, separated from the earth, divorced from their roots. And the design expresses this as well, the uprooting of the families, who were then destroyed and scattered in all directions. Right here, for example, we're standing in front of the story of the Habermann family from Eastern Poland, a Polish-speaking, Jewish, bourgeois family, that after 1941, got caught in in the terrible persecution by the German occupiers and the German SS. The mother was deported to an extermination camp, the father forced to work as a slave labourer in the oil industry, the family managed to save themselves again and again from the continuous shootings by going into hiding, always alternating between being in hiding and working as slave labourers. And at one time, the daughter, Sabina, was discovered and photographed, when she was found in one of these hiding places. This photo is still existing, because a local Polish photographer had kept it in his archives and gave it to her after the war. And that is actually the exception, as generally most of these family histories here with all these photos are exceptions. Most families vanished without a trace, they were murdered without leaving any traces of their existence. 4. Room of Names Well, when you leave the room of Family Fates and go into the Room of Names, you first encounter darkness and all you see is one name being projected. You begin to hear a story – just sound coming from speakers. A story is told and the images have to be formed in your head. The visitor has to sit down and listen to the story being told and the images of the various lives must be created by him- or herself. Six million murdered Jews is a figure that is wholly incomprehensible. We selected 600 stories from this enormous amount and when a visitor enters this room, he/she hears a story, and in that instant, this one person is seized from anonymity. 5. Room of Sites Here, in the Room of Sites, 220 places all over Europe are shown, representative for all the sites of persecution and annihilation. You know, it was important to us to present the Jewish setting, in this case, via these individual sites. Similar to the Room of Families, the idea was to show, that this crime did not simply come from nowhere – rather, we wanted to demonstrate: these were wholly intact social environments – inasmuch social environments can be intact – and it was then, at these sites that this and that transpired. In addition, we wanted to use this room to show how many sites there are in Europe that are unknown, not necessarily sites that have been forgotten, but places most people know nothing about – and it was these sites that we wanted to make people aware of. Take this into consideration: some deportations from Polish ghettos sent more people to their deaths on a single day than were killed brutally in some concentration camps during the entire existence of that camp – that's really what we wanted to communicate. There's a letter about a mass shooting in Marylow, Belarus in the Fall of '41. And I seem to recall that it was a man, who was the father of a family writing, I believe a state official, postal agent in Vienna or something like that, and he had his own family. And so he's writing to his wife, who is sitting at home in Vienna with, I think, 2 children, how amazing it is to see the Jewish babies flying through the air and how great it is to shoot them down. And this is a document that always leaves me shaking my head in astonishment. Because when you have your own family, you have two children of your own, to be a part of something like this and then to even describe it the way he does, just shows how profound the seed or the roots of this anti-Semitism were. Just this feeling or this insane ideology: Jews must be annihilated. And that applies to babies just as much as it does to the aged. That was really one of those documents where I just sat there decided to go home earlier. 6. Present Coming out of the exhibit where the development of the Holocaust is presented historically, i.e. – what was going on between 1933 and 1945, we then enter Foyer 4 and are in the present, and are not showing the events themselves, but rather the memory of them, the commemoration of it all, the commemorative culture with regard to the Nazi persecution throughout all of Europe. And in this Information Centre the database of names of the Jerusalem Holocaust Memorial Yad Vashem is available. Visitors can go to the terminals, and search for individuals, for people, for names, for places – if I want to know who was murdered in the Holocaust from my place of birth, I can enter the name of the place and will – usually – find a certain number of people who were murdered in the Holocaust. I was imagining, that when you walk through the Field of Stelaeas a visitor, and you see these blocks of concrete, that are initially totally detached from any kind of content, but that when I take up this formal aspect, here in the Information Centre, and then convert this form into a medium of information, and re-interpret them, so that subsequently the visitors of the exhibit see the Field of Stelae with different eyes and associate this content with these shapes, that they first saw here. I'm going to bear a tremendous sense of oppression with me and the exhibit impressed me. Impressed me very much. There's so much that stays with you. Indeed. I am totally speechless. I can’t comprehend it . It affected me deeply. I feel like, when you leave this place, you become quiet and thoughtful – again and again. In the entry area, the photos of five or six people, large sized portraits. These are personal stories, to be discovered behind the images… When I heard that a huge field of standing stones was going to built here, I thought, well, okay, what's that going to turn out to be – but now that you've gone down here and seen it, then you understand it all right. Well, the time I felt most strongly affected here at this memorial was during the conversation with the Auschwitz survivor, as he, in his sonorous voice, reported for over two hours on the most horrifying barbarities that he had witnessed at Auschwitz and experienced himself and then suddenly burst into tears, as he was telling how he was reunited with his mother here in Berlin. And this mother, who had long given up the hope that she would ever see him again, given up hope he would ever return – that was a very moving moment. Or when you have a visitor saying: I lost my Grandmother in Auschwitz and she was murdered there, she was cremated and I don't know where her ashes are. And this visitor takes a stone and places it on one of the stelae that is not dedicated, not individually inscripted and says: This stele now belongs to my Grandmother. And you have to indeed confirm: This man is right! We must be aware of what happened to the Jews. We must be aware of the things dictators are capable of concocting. And we must learn: Never again. And put up resistance. But early enough and right from the start. When something like this begins to develop, you must be careful, offering resistance and saying: No, we refuse to accept this. And when the young generation learns this, and also the older generation, but especially the young people, then that is something that we wanted to accomplish with this memorial and perhaps are able to accomplish. BONUS TRACKS What were the main aspects of the discussion on the Degussa company's participation? The discussion regarding the involvement of the Degussa company pertained to something very fundamental. Although this company was only involved in, shall we say, the final level of the whole construction process, with an additional product, or was responsible for such, this discussion was indeed one of something very, very fundamental and thus also to a great extent, dangerous. The core issue was whether a company, that participated in a central way during the Nazi era, namely in the death of many people, can this company today, still continuing to exist 50 years afterwards in Germany, be a part of such a project? If I can phrase it that way. And there were indeed people who said: that is not possible, that cannot be. And the question was: if you apply this criterion, that a company cannot participate due to its historical role, if you apply that criterion consistently, and taken that further for such a project as this one, then the outcome would have been that this project could not be built with any German company. And essentially, you wouldn't be able to build it in Germany. This is to say that the idea, that the German people have learnt just that and demonstrated, that they are able to draw conclusions in this regard, to take on a new attitude, this conclusion would no longer have been feasible. If you applied this ultimately. How were the stelae made? The sides are about 16 or 17 cm thick, both here and over there. And the stele, when poured in the factory – it is produced in a factory, because guaranteeing constant conditions is only possible in the factory. And then the stele is poured upside down. So the hollow end is pointing upwards and this is how very much material was saved, which also meant that transportation expenses were reduced considerably. And on the other hand, this hollow-shape production method allowed the concrete to set better as it dried better, improving the processing of the concrete. It really was a very interesting production process: pouring the stelae in this fashion, then having them erected here, transported and then positioned on-site with a crane on the foundations, which by the way, made use of a precisely conceived positioning system, which was also fascinating, as each stele had a slightly different tilt. Are all the stelae the same? The unique thing is, is that each stele has the same basic dimensions, but each stele is different in certain aspects. Each stele has individual height, tilt, alignment and is unique in its positioning within the Field of Stelae. There are steles measuring 1.7 meters in various parts of the Field of Stelae: one in the ascendant part of the field, one in the descending part and slanted – so this really affects the viewers’ perceptions. This material never seems the same, it is greatly influenced by the respective angle of the sun rays, by the pattern of clouds in the sky. Today it is sunny, blue skies, or when the skies are grey, or white, when the sun is setting – this really creates an unbelievably varied spectrum of perceptions of the Field of Stelae and this is an artistic process the architect consciously sought and at which we all intensely worked at, because it has to do with all the tilting, the alignments, the colouring of the material and the positioning. How were the family histories researched? We researched most family histories in such a way that we tried to locate collections of photos or we placed advertisements and people living back then contacted us. But we also had the exact opposite case where there was a photo everyone was familiar with, or a series of photos that were very famous and where colleagues from other museums had already done the research: who is actually in the picture, who can we identify? This was what we did with the famous pictures of the arrival of the Jews, of the Jews from Hungary. There's a photo of a mother standing next to her child in a stroller, right after arriving. And with help from our American colleagues, we were able to contact the family, the survivors and to get photos, and photo albums from before the war, and then, in this case it wasn't even an album, but just a few photos that are still existing, and then to tell this story. Starting with their life during peacetime, before the occupation of their hometown by the Hungarians, then by the Germans, and then on to the deportation. How did survivors of the families react to this room? Well, in May, 2005, we had invited family survivors and they were naturally deeply moved when they crossed the threshold into this room, very moved, many tears were shed, a tribute really to their family members who had been murdered. There was, for example, a family who said: we will return here again and again, we now have a kind of grave for both our relatives who were murdered and did not have a grave, were buried without a grave. And for us this is something completely different than what we had expected: we are a museum and we will continue to work here and perhaps in 2, 3 years we will show other family histories. Of other contacts we made. We probably will not do that, because, essentially, this is something final, because it pays tribute to those who are here, and it is also a kind of commemorative chamber. Does the memorial harm the historic sites of remembrance in any way? Well, we also refer to other memorial sites in this section of the exhibit because we want to make it totally clear from the start that this memorial is part of a whole commemorative network. There were those who were afraid this memorial would distract attention from the historic sites and the memorial is not an historic site, it is an artificially created site, though in retrospect, it has become evident that this memorial serves as a kind of 'lighthouse' memorial, guiding the attention of the public to this topic much stronger. And this attention is something that the other commemorative sites benefit from, and they have recorded even higher numbers of visitors. How were the portraits shown in the entrance foyer chosen? How many we researched in all – well, something between two and three hundred. I can't say exactly, I can't remember exactly at this point because there was quite quickly a process that reduced the basic selection – we were looking for portraits where people were looking straight at the camera. And that is something photographers always say in their studios: do NOT look right into the camera – which meant that this significantly reduced the number of pictures available for selection. We wanted, however, to have this direct look into the camera, in order to achieve the following effect: the visitor feels as if he is directly adressed due to the subject of the photo looking straight at the camera, in a virtual way, but feels this strongly and is thus drawn into the exhibit. So we were looking for portraits of people looking right at the camera. They had to be historic photos, had to be, because the people had died or were murdered and the original images had to be of very, very good quality so that we could show them in this size. This meant basically that the number of available photos was reduced drastically. Because, for example, snapshots are often out of focus and many other things mean that an image was not suitable for this large-scale presentation. And once we had clarified these technical things, we were able to sift through 100 to 150 photos according to more detailed criteria. And that's where we decided to establish 6 regions of origin in Europe, the number 6 came from the architectonic requirements here – we don't have space for any more. So we had 6 different regions throughout all of Europe, then men, women, children, i.e., a three-part classification, then there were various religious environments to be considered, all somehow visible within the photos selected if possible. And the sites of the deaths were to reflect these 6 different regions in Europe – be it in the death camps, one of those, or in the mass shootings or at home, in front of their houses, as many different types of murdering as well, to make it palpably clear that this killing was going on throughout Europe. Which photograph was particularly hard to decide on? Well when you look at this photo, on the left, the little girl, look at it more closely, then you will see that all these technical criteria I referred to are only somewhat fulfilled – i.e., the photo is quite blurred. However, it's a picture of a young girl who was very much alive, which was also one of our selection criteria: we didn't want any passport-type photos, for example, when people were being registered at Auschwitz, but images of living, real people. And this was a photo of a young girl, a snapshot from a family photo album and where her vitality is very distinct – in contrast with, for example, a studio photograph, where children are stylised and then even have a teddy bear in their arms and thus don't seem quite as vivid. And that's why it was very important for me to include this image in the presentation, even though initially it did not entirely fulfill the technical selection criteria. But today we have so many attractive technical options for enhancing the original photo, which meant we could greatly improve the original, and that's what we did. What was your most intense experience in the Information Centre while serving as a visitors' guide? Another example, an example that was no less strenuous, but very satisfying, was the visit of an Auschwitz survivor, with whom I had a 7 hr. conversation. This person made the fact that he had survived Auschwitz and a large part of his family and his friends did not, was only able to deal with this by taking on the task of reporting about these events. And after half an hour of conversation, I decided to go to the little kitchen with him and to continue the talk there. And that was a conversation where I learnt so much, more than you could ever learn in any communication seminar and in any history course. And I am so glad I had that opportunity but I was soaked with sweat afterwards and could not get to sleep that night. But this is an occupation that I find immensely satisfying, if you are actually able to help a person that survived all this, what we are commemorating here. What was your first impression of the memorial? I was surprised that the Field of Stelae is so small. I had thought it would be much larger, I had thought it would be like a huge giant, but when you see how the stelae are placed in a depression, and you look over all the stelae, and can see the pedestrians walking by on the other side of the Field of Stelae – that was surprising. It is smaller than I had thought and after going through the Information Centre, I was certain that what Peter Eisenman said at the inaugural ceremony is correct: this memorial gains its ability to transmit its uniquely powerful statement via this Information Centre. The aesthetics of the memorial are not that abstract, such that someone could interpret them as being totalitarian or fascist, certainly not. Why?, well, because the Stelae are all individualised, with their unique height, tilt, that interpretation doesn't fly. But otherwise, there is plenty of room for interpretation and in order to make unambiguously clear why/why not this memorial was built – that's what the Information Centre is for. And I felt that way the very first time I was in the Information Centre. What was the most surprising talk you had with a visitor? This memorial works from two different perspectives: there was a man who visited the memorial who had perpetrators in his family background and he said: being at this memorial gave him, for the first time, the opportunity of putting himself in his father's situation back then, where the father had claimed he agreed to be part of a system that was much more powerful than he and he had underestimated that, and he only became aware of how dark and powerful this system was once he was extensively involved in that system. Now, of course, one can argue extensively whether or not that is a permissible description of his father. But what I learnt from this visitor was that this memorial is relevant for people whose families were the perpetrators, and that it helps them to deal with this subject, genocide, which they are better able to do, than without the memorial. What made the strongest impression on you? What impressed me most was a group of tourists consisting of emigrant Jews, formerly German citizens along with their younger relatives and friends from Israel and the United States. And that's where the people in this group of tourists live as well. And they said to me: "We had never planned to visit Germany. We had even vowed never again to visit German soil. But after you Germans", and this is a German memorial, in Germany, not a memorial built by the nation of Israel or a Jewish interests association, rather the Bundestag, the German parliament decided it would be built, "After you Germans stated you wanted to build this memorial, we got curious about you and wanted to get to know you, see what you're like, these people willing to tackle and realise such a project.“ "Because we have the impression that in the other countries, this would not have been at all possible. And we got curious about you." And that is something that makes you really happy, when you see the message of this memorial is understood elsewhere. How were the biographies chosen for the Room of Names? Well the selection of the names presented here, of the biographies, it was especially important for us that a sense of proportion is maintained. This would initially seem to be a mathematical term, but if we imagine that 3 million Jews were murdered in Poland alone, then at least half of the names presented here have to be of Polish Jews. Another aspect is perhaps the balance between genders, such that women, men and many of those murdered were children, and we show that here. Where does the data originate for the database of names? The source of the data in the name database of Yad Vashem are what are referred to as Pages of Testimony. These are forms that have been filled out since the 1950's by acquaintances, relatives of Holocaust victims. These forms are where people give testimony: Yes, I know, my Grandfather, my Grandmother, perhaps even my father or mother were killed in the Holocaust, and they were born on such and such a date, and were likely murdered in this town. How extensive was the research work for the Room of Sites? The effort expended particularly for these and other rooms was immense – and took place throughout Europe. I myself was in Warsaw several times at the Institute of National Remembrance. I visited some small Polish archives, I went to Grodno in Belarus with a portable scanner to scan a document, but of course, the most difficult thing was getting the painting of the Belzec concentration camp transported here. We worked years having a reproduction of it made in Poland on-site. The painting there rests on the floor of the village, or well, yes, the village parish but it wasn't possible for us to organise a suitable reproduction. I went there myself sometime end of 2004 in order to speak with colleagues and to make clear to them exactly what it was we needed. In the end, nothing came of it – once again. Then my colleague Katharina and I got into the car and drove to Belzec. Before departing, we had obtained a written authorisation from the next-largest city, Zamosc, that we were permitted to borrow this painting. So we drove there, borrowed the painting, had it reproduced here in Berlin and then returned it. Belzec is about 1,600 km from Berlin. That was quite an effort but it was an exciting trip inasmuch that it was a journey through a cultural setting or a former cultural setting, Galicia, that was rather like a journey through the Room of Sites. To the left, to the right and straight ahead there were many places that we have on display here. Is the memorial debate now over? Once this memorial was inaugurated, was handed over to the public, the debate did not simply cease. Discussions continue. How to treat this memorial is an issue and it continues to polarise people. It remains, so to speak, a field of stumbling blocks. People are unnerved – but that means we have accomplished something. Because when something unnerves people, they wonder: what does this memorial stand for. And them posing these questions signifies that we are moving forward. It signifies that they are posing questions, and they get answers. And it doesn't have to please everyone – it is a question regarding art, and art, as everyone knows, is a debatable point. Whether or not you should debate this is another question, particularly concerning modern art. But as long as this memorial remains a stumbling block in a positive sense, it has attained its goal. And as long as people actively confront this memorial and its commemoration – and people are doing that – in the Field of Stelae, by sitting down and discussing things, the memorial definitely has fulfilled its mission and it demonstrates that this is not a final verdict in stone, but rather a transition to a different form of debate. How was it decided to locate this memorial in such a central location? Back in 1988 there was this initiative to erect a memorial in Berlin for the European Jews who were murdered – a memorial in the city where this genocide was planned and organised – to erect a symbol. A symbol of the responsibility of the non-Jewish Germans towards the victims, towards this crime, a commitment. And a symbol of commemoration and for a tribute to the victims. Then there was much, much debate – all of which I cannot relate here, nor describe the reasons for them, or especially, how they developed – about the dedication, and also about the location. And finally, it was decided to select a location which is prominently in the middle of the city, next to the Brandenburg Gate, close to the Reichstag building, the seat of the German parliament, to make it perfectly clear: Yes, we are willing to face this crime, here in the center of our German capitol city. How did you come up with the idea for this memorial? I didn't come up with the idea. The idea originated with the historian Eberhard Jaeckel. We had filmed a large production at ARD, a German public television station, about the murder of European Jews, a 6 hour documentation, the longest that had ever been done to date on German television and we were in Israel, conducted interviews with survivors there. And while we were at Yad Vashem, Jaeckel said: look, we have to have a memorial for the murdered European Jews in Germany. And I found the idea totally convincing, I said: yes, we shall do it. And I returned to Berlin, was the chairperson of a citizens' movement and proposed this to my board, this was 1987/88. And then we decided we want to erect a memorial to the Jews in Berlin. Back then we didn't know it would take 17 years to realise this and we were convinced that it had to be a memorial devoted to the Jews exclusively. We discussed that quickly and came to that conclusion because we felt, the murder of the Jews was the primary, the most significant aspect of Hitler's annihilation policy. It was more important for him to murder the Jews than it was to win the 2nd world war. And that's why we said that this was the main conviction of Hitler's followers, the Nazis. At the same time, we always supported efforts to erect memorials for other groups of victims. Where did you draw the strength to fight all these years for this project? Yes, we were of course, at all 6 annihilation sites with our film teams, with our camera crew, Eberhard Jaeckel and I. And we were in Belzec. And we had a Polish interpreter, but back then this person was also a 'watchdog', but she was a very nice woman who was very committed to this subject. And she informed me that in the sand next to Belzec, next to the long graves, there are teeth. And then we did find a molar. And I put this tooth in my hand. I didn't want other people to walk over it with their shoes, the area was an open area, and everyone was just walking around. Then I put this tooth in my hand and never let go of it and I said, together with Eberhard: We swear to you, that we will erect a memorial. Describe how you felt when everything was finally completed? We were glad, glad. Not happy. That's a different feeling. But we were glad and we said: it was right to fight this long, difficult battle and it was important that we fought it and this is what we hear from the reactions of the many visitors, from Jewish visitors as well. I was just talking with a Jewish woman from the United States, who was visiting the memorial, and she said: she thanks us, she thanks us in a heartfelt way, that we have done this thing. Her mother was murdered and this here is for her mother also. And that is how we have always viewed it. What was your initial idea for designing the Information Centre? When we started this task, I imagined that this Information Centre would be positioned below the Field of Stelae and imagined how all of it would come across as a whole. The existing architecture of the Field of Stelae, the rooms below the memorial, the exhibit rooms and their contents. How to unify all that in one formal design. And due to the powerful architectonic mandate of the memorial, I came up with the idea of taking up the formal aspect and continuing it in the exhibit rooms, in a related fashion. For example, a room where this is most evident, is how it's as if the stelae, the memorial stelae above ground grow through the ceiling of the room, and then open up and become exhibit modules, bearers of information. And here in the room, the illuminated glass panels with the quotations are exactly in the same dimension, the same size, the same proportions of the Field of Stelae, it's as if they reflect the blueprint of the Field of Stelae overhead. What was especially important to you? My main focus was putting the informational content in the foreground and to provide this with a dignified framework. My primary desire was to provide the contents, the quotations of the victims or the photos with a space, such that the effect would become evident, without all too much peripherals. And I just did not want to provide interpretation, rather simply the documents and the statements themselves – allowing them to speak for themselves. What ought visitors to carry away with them from the Room of Dimensions? I want visitors to primarily retain the individual histories, the fates of these people, that they experience what happened 6 million times, and to 6 million individuals. Of course, we cannot display the fate of each of the 6 million here, but have selected a few to represent them all, and these few are able to powerfully speak – and every visitor can imagine for themselves what this all means, the extent of it all. Each person's life is so vast and so complex. That is what we want to show here and every visitor and multiply that by 6 million for themselves, in order to grasp the dimensions involved here. Were there obstacles having to do with the actual design? Before we actually made a decision that we were going to present the quotations on the ground, there were definitely some vehement discussions about this. For various reasons. Some people were against this as they felt like people would be stepping all over these quotations if the quotations were on the ground. My viewpoint, however, was that people would walk along the perimeter out of respect. But there was that fear, that had to be taken seriously. Another one was that this type of presentation would be all too sacred in nature and that was also a cause for concern. And there were those who maintained that people would be reminded of gravestones and I think, however, that because they shine and because they communicate very personal words, I don't think people will associate them with gravestones. How was a decision reached? The Board of Trustees, responsible for making the decision whether or not these quotations would be presented on the ground or not, really did not make things easy for themselves. I believe that this decision-making process lasted about a year. And for a long time, there no decision was made until finally a 1:1 sized presentation was done, in a room similar in size, and with these engravings on the ground. And the Board of Trustees were able to walk through this prototype room and admitted that their fears had not been confirmed. Then there was a vote, and a majority decided this is the way it would be done.